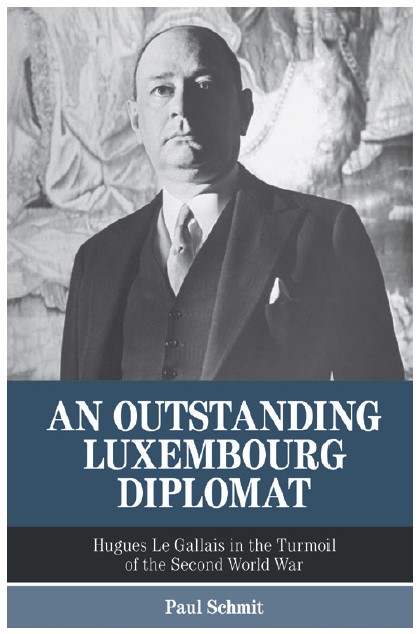

The life and work of Hugues Le Gallais have become increasingly familiar to me over the last twenty years or so. With ups and downs, more or less intense research depending on my availability and my hobbies, I have always learnt more about a multi-faceted character whose trajectory I have crossed several times with a few decades in between. At the end of 2001, I was appointed Deputy Chief of Mission of the Embassy of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in the United States and came across several traces left by the first resident head of post in Washington.

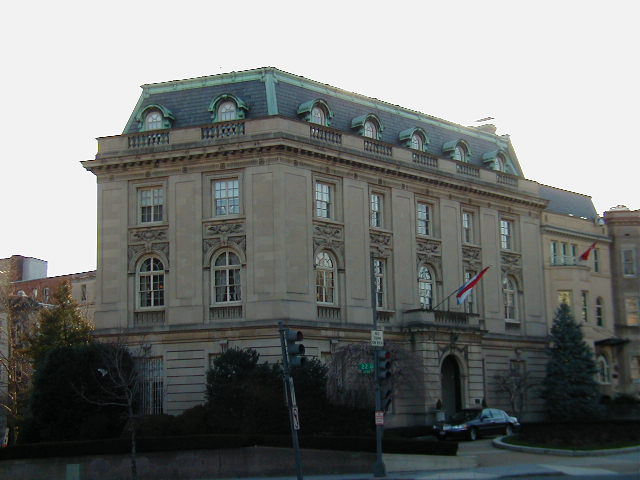

Le Gallais had lived and worked for almost 18 years at 2200 Massachusetts Avenue, in what is still, today, the Luxembourg Embassy. Most of the documentation on Ambassador Hugues Le Gallais, especially his correspondence with Luxembourg’s political actors, has been in the National Archives of Luxembourg since the summer of 2002, having been inventoried just after my arrival at the Embassy as a young diplomat. This exchange of letters with a wide variety of personalities covers both everyday aspects of the life of Luxembourg exiles during the Second World War and political and economic issues.

Analysing these documents at the National Archives in Luxembourg was a great help, as was the additional insight provided at the end of my research by a few very personal letters handwritten by Le Gallais to the Grand Duchess and made available to me by the Archives of the Grand Ducal House. This allowed me to discover another side of the diplomat Le Gallais, who was also Chamberlain to the sovereign. During the years of exile, he had to work tirelessly and find his way between the Head of State and the two main members of the government, Minister of State Pierre Dupong and Minister of Foreign Affairs Joseph Bech, regardless of whether they were in the United States, Canada or the United Kingdom.

Numerous meetings in the United States, but also in Luxembourg, Germany, France and Italy have given me an even fuller picture of an outstanding diplomat, sometimes criticised or even mocked, who has led a very different life from that of today’s diplomats. His family members, friends and contemporaries who knew Le Gallais are now increasingly rare to be able to testify. Several meetings with the son and grandson of the Ambassador in Venice in 2018 gave me answers to my many questions and allowed me to see the photo albums, be it of the Japanese or American stage of Hugues Le Gallais’ career. Other members of the family helped to flesh out and even corroborate certain aspects of the busy life of Le Gallais and his entourage. Another invaluable source is the scrap book that Le Gallais’ secretary, Eleanor Maloney, had compiled during her 18 years in Washington. She gathered extracts from press articles about the Luxembourg Embassy and added photos and other documents, such as seating plans and menus from major Washington dinners. Part of Ambassador Le Gallais’ correspondence with Madame Maloney was handed over to me in 2004 by her daughter.

An essential contribution in trying to understand Le Gallais’ action during the Second World War are the books and publications of many authors, among which I would like to mention those of the former Luxembourg Ambassador to the United States, Georges Heisbourg, on the Luxembourg government in exile. At the National Archives, I was able to view the documentation left over from his detailed research in the 1980s. It is undoubtedly difficult for Le Gallais’ successor as Ambassador to draw an objective and accurate portrait of him. I have drawn inspiration from several studies and publications on this difficult period for everyone, also the most critical and recent ones. Research at the National Archives at College Park has wisely supplemented these sources.

I don’t want to take sides or put into question, let alone judge, but simply try to better define and relate the character. In essence, I agree with the theme of an exhibition at the Musée de la Ville de Luxembourg in 2002: “Et war alles net esou einfach” (Everything was not that simple). This formula also applies to a diplomat like Le Gallais, by definition far from the heat of military action or active resistance in his native country. Or to state with the writer and journalist Alfred Fabre-Luce: “It is always difficult for the historian to reconstruct for a subsequent generation the atmospheres of an era. A man who looks back tends to assume already known at a certain moment what will only be known later.”

Consultation of other sources was, of course, essential to retrace the fabric of a diplomatic life rich in often fascinating adventures. Thus, the Library of Congress was a great help, but also a site allowing to obtain or check information remotely in all the articles of the American press.

The present study of the life of a scion from a family of industrialists, who became a businessman or rather a commercial representative and, later on, the first Luxembourg diplomat to reside in the United States, commits only its author. The opinions and reflections, or even interpretations and comments, do not reflect those of the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs or the Luxembourg government. As the saying goes: “All errors due to erroneous interpretation or transcription in this account are the sole responsibility of the author.” I wanted to express myself in a personal capacity and give this testimony about a Luxembourg diplomat who is necessarily marked by subjectivity. It is not a question of glorifying a character or of writing a scholarly and detailed biographical story, but rather of trying to better understand and bring to life the broad outlines of a personality and his work and the many written and photographic traces left by Le Gallais. Not being a historian, I do not wish to enter into any polemic in relation to the activities of the sovereign and the government in exile in relation to atrocities suffered by most of those who remained in the country.

To the right of the Grand Duchess, her mother Grand Duchess Marie-Anne, and the American ambassador D. H. Morris. Behind the Grand Duchess, her chambermaid Alice Sinner, Mrs. Konsbruck and her son Carlo Konsbruck, Countess de Lynar, Grand Duchess Marie-Anne’s lady-in-waiting, aide-de-camp Guillaume “Guill” Konsbruck, and the chargé d’affaires Hugues Le Gallais.

What I found fascinating in trying to piece together the puzzle of Le Gallais’ career is to come across many actions and reflections, even reflexes, that remain in a certain way and within certain limits in diplomatic life today. Without wishing in the least to idealise or systematically justify Le Gallais’ action, I have often wondered whether, at another period in our history and with other means, we are not, in the end, motivated by the same ambitions for our country and our career, our professional life and our private life. Above all, I wanted to place the complex itinerary of Le Gallais in its historical context and try to make his public and personal action, as well as his intimate aspirations, more comprehensible. Le Gallais’ participation in numerous international conferences that have led to multilateral institutions that are still relevant today, as well as his interaction with very high-ranking representatives of the most diverse countries, no longer necessarily reflect the daily reality of all those who today work in the diplomatic arena. In short, I have tried to immerse myself in Le Gallais’ family and social background in order to realise that he has had very little contact with people from a less affluent background than his own.

To my knowledge, this biography is the only one that tells the story of a Luxembourg diplomat. Few politicians of this country (Emmanuel Servais, Nik Welter or, more recently, Pierre Werner) have published their memoirs, like Ambassadors Auguste Collart and Adrien Meisch. I dare to hope that this gap will one day be filled by other essays of this kind or that other research on a pivotal period in our history will come to fruition.

Finally, let me inform the reader, out of a concern for honesty, but also because of family loyalty, that I wrote these pages in the knowledge that one of Le Gallais’ privileged interlocutors, at least during the Second World War, was my wife’s paternal grandfather. This connection with a man whom I did not know personally did not make things any more obvious, but I hope that by stating this fact at the outset I will help to prevent a mixing of genres while avoiding the reproach of indirect glorification.

Everything that follows, based on chance encounters and assiduous research, is therefore only a modest contribution, so as not to let an outstanding diplomat, a special and singular character who is nevertheless interested in the good of his country and his people, fall into oblivion.

“The diplomatic body is never a beautiful body; it is often a body that’s aged; at times it is a wise body, but it is always a body at the feet of the minister of foreign affairs… Good embassies are those that make no noise and whose activities are conducted without fanfare. Like happy peoples, they will have no history… Like children, diplomats should be seen, not heard. The less they say, the more they will be heeded.” Quote of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand found in the papers of Hugues Le Gallais